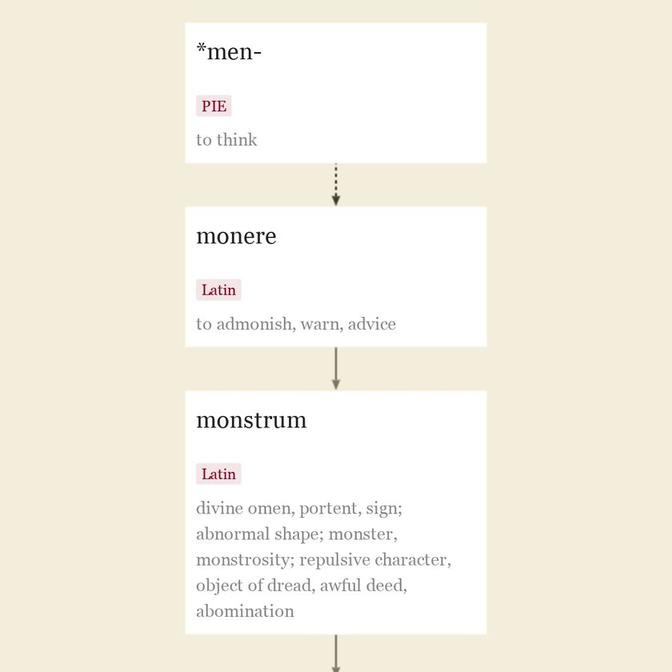

early 14c., monstre, “malformed animal or human, creature afflicted with a birth defect,” from Old French monstre, mostre “monster, monstrosity” (12c.), and directly from Latin monstrum “divine omen (especially one indicating misfortune), portent, sign; abnormal shape; monster, monstrosity,” figuratively “repulsive character, object of dread, awful deed, abomination,” a derivative of monere “to remind, bring to (one’s) recollection, tell (of); admonish, advise, warn, instruct, teach,” from PIE *moneie- “to make think of, remind,” suffixed (causative) form of root *men- (1) “to think.”

Abnormal or prodigious animals were regarded as signs or omens of impending evil. Extended by late 14c. to fabulous animals composed of parts of creatures (centaur, griffin, etc.). Meaning “animal of vast size” is from 1520s; sense of “person of inhuman cruelty or wickedness, person regarded with horror because of moral deformity” is from 1550s. As an adjective, “of extraordinary size,” from 1837. In Old English, the monster Grendel was an aglæca, a word related to aglæc “calamity, terror, distress, oppression.” Monster movie “movie featuring a monster as a leading element,” is by 1958 (monster film is from 1941).

“huge, hideous, or terrible marine animal,” 1580s, from sea + monster. Sea serpent is attested from 1640s. In Middle English a sea-monster might be called sea-wolf; in Old English, sædraca “sea dragon,” or sædeor “sea-animal.”

“capable of being proved or made evident beyond doubt,” c. 1400, from Old French demonstrable and directly from Latin demonstrabilis, from demonstrare “to point out, indicate, demonstrate,” figuratively, “to prove, establish,” from de- “entirely” (see de-) + monstrare “to point out, show,” from monstrum “divine omen, wonder” (see monster). Related: Demonstrably.

“venomous lizard of the American southwest” (Heloderma suspectum), 1877, American English, from Gila River, which runs through its habitat in Arizona. The river name probably is from an Indian language, but it is unknown now which one, or what the word meant in it.

late 15c., “an appeal, request,” a sense now obsolete, from Old French remonstrance (15c., Modern French remontrance), from Medieval Latin remonstrantia, from present-participle stem of remonstrare “point out, show,” from re-, here perhaps an intensive prefix (see re-), + Latin monstrare “to show” (see monster).

The sense of “a strong formal representation of reasons or statement of facts against something complained of or opposed” is from 1620s. Also in history with specific political and ecclesiastical senses. Related: Remonstrant (n., adj.).

1550s, “point out, indicate, exhibit,” a sense now obsolete, from Latin demonstratus, past participle of demonstrare “point out, indicate, demonstrate,” figuratively, “prove, establish,” from de- “entirely” (see de-) + monstrare “point out, show,” from monstrum “divine omen, wonder” (see monster), and compare demonstration.

The meaning “point out or establish the truth of by argument or deduction” is from 1570s. The sense of “describe and explain scientifically by specimens or experiment” is from 1680s. The meaning “take part in a public demonstration in the name of some political or social cause” is by 1888. Related: Demonstrated; demonstrating.

Latin also had commonstrare “point out, reveal,” praemonstrare “show beforehand, foretell.”

late 14c., demonstracioun, “proof that something is true,” by reasoning or logical deduction or practical experiment, from Old French demonstration (14c.) and directly from Latin demonstrationem (nominative demonstratio), noun of action from past-participle stem of demonstrare “to point out, indicate, demonstrate,” figuratively, “to prove, establish,” from de- “entirely” (see de-) + monstrare “to point out, reveal show,” which is related to monstrum “divine omen, wonder” (source of monster). Both are derivatives of monere “to remind, bring to (one’s) recollection, tell (of); admonish, advise, warn, instruct, teach,” from PIE *moneie- “to make think of, remind,” a suffixed (causative) form of the root *men- (1) “to think.”

Sense of “exhibition and explanation of practical operations” is by 1807. Meaning “public show of feeling by a number of persons in support of some political or social cause,” at first usually involving a mass meeting and a procession, is from 1839. Related: Demonstrational.

early 14c., moustren, “to display, reveal, to show or demonstrate” (senses now obsolete), also “to appear, be present,” from Old French mostrer “appear, show, reveal,” also in a military sense (10c., Modern French montrer), from Latin monstrare “to show,” from monstrum “omen, sign” (see monster).

The transitive meaning “to collect, assemble, bring together in a group or body,” especially for military service or inspection, is from early 15c. The intransitive sense of “assemble, meet in one place,” of military forces, is from mid-15c. The figurative use “summon, gather up” (of qualities, etc.) is from 1580s.

To muster in (transitive) “receive as recruits” is by 1837; to muster out “gather to be discharged from military service” is by 1834, American English. To muster up in the figurative and transferred sense of “gather, summon, marshal” is from 1620s. Related: Mustered; mustering.

c. 1600, a kind of sea monster, part horse and part dolphin or fish, often pictured pulling Neptune’s chariot, from Late Latin hippocampus, from Greek hippokampos, from hippos “horse” (from PIE root *ekwo- “horse”) + kampos “a sea monster,” which is perhaps related to kampe “caterpillar.” Used from 1570s as a name of a type of fish (the seahorse); of a part of the brain from 1706, on supposed resemblance to the fish.

before vowels terat-, word-forming element of Greek origin, used from 19c. and meaning “marvel, monster,” from combining form of Greek teras (genitive teratos) “marvel, sign, wonder, monster.”

This is reconstructed to be from PIE *kewr-es-, from root *kwer- “to make, form” (source also of Sanskrit krta- “make, do, perform,” Lithuanian keras “charm,” Old Church Slavonic čaru “charm”).

Source: O

etymonline.com

oxford dictionary